Dissertation Handbook Masters in Public Health and Masters of Research Public Health/Primary Care

Academic Year 2021/22

This handbook is for those of you embarking on the 60 credit dissertation of the MPH or the 90 credit dissertation of the MRes in Public Health/Primary Care. Refer to Blackboard MPH Programme Community / Dissertation and Critical Review for additional guidance and support. Use this handbook in conjunction with the Programme Handbook (MPH and MRes) and Faculty/University regulations.

Important Contacts

| Course unit leads | |

| Dr Roger Harrison | roger.harrison@manchester.ac.uk |

| Dr Andy Jones | andrew.jones@manchester.ac.uk |

| Programme Director | |

| Professor Arpana Verma | mph.director@manchester.ac.uk |

| Programme Administrators | |

| MPH Admin Team | mph.admin@manchester.ac.uk |

Introduction

This handbook accompanies the main MPH/MRes Programme Handbook and other programme and University information. It is essential that students understand the requirements and expectations as set out in these documents, to support their academic studies. Please be aware that the requirements, pathways and options regarding the dissertation have changed for existing and new students at the start of September 2021. These changes are included in this Handbook. Additional resources provided in Blackboard/MPH Programme Community/Dissertation and Critical Literature Review. Be sure you understand the following:

| Academic year | September 2021 to September 2022 |

| Dissertation | Usually refers to the actually written piece of work that has to be submitted (through Blackboard) for marking |

| Dissertation Unit | This refers to the actual ‘unit’ just like a course unit |

| Dissertation options/frameworks | There are a number of types of dissertation options which students can use to then base their dissertation within |

| Dissertation proposal form | This is submitted once a student has decided upon the focus for their dissertation. Once submitted they will get their supervisor |

| Dissertation proposal submission dates | There are five times a year when students can submit the proposal form above. This are fixed closing dates. This is not the date for submitting the finished written dissertation |

| Dissertation submission date | This is the final date and time by which the finished dissertation MUST be submitted. Just like an assignment, penalties will follow if it is submitted, unless formal agreement has been given through the Programme Director and the MPH Admin team. |

Online resources

An introduction to the dissertation is given as part of the programme Induction.

There is a section in Blackboard in the MPH Community Space that provides further information and resources with regards to the dissertation. We strongly recommend ALL students explore the range of resources that we have created for them in this part of Blackboard/MPH Programme Community/Dissertations and Critical Literature Review.

Online tutorials/webinars

Students starting their dissertation or Critical Literature Review are encouraged to attend the following. The value of these sessions will be increased as more students participate directly. Sessions will be recorded but please make every effort to attend some of these. The Masterclass Series will be of direct value to MPH/MRes students:

| Masterclass Series – note the different start times (all UK time) | |

| Date | MPH/MRes Topic |

| Tuesday 28th Sept. 2021 | Isla Gemmell – 15:00hrs: Analysis of existing quantitative data |

| Tuesday 5th October 2021 | Greg Williams – 16:00hrs: Primary research study |

| Tuesday 12th October 2021 | Christine Greenhalgh – 16:00hrs: Analysis of existing qualitative data/theoretical project |

| Tuesday 26th October 2021 | Andrew Jones – 16:00hrs: Research Grant Proposal |

| Tuesday 2nd November 2021 | Lucy O’Malley – 16:00hrs: Systematic reviews |

| Tuesday 9th November 2021 | Roger Harrison – 16:00hrs: Public Health Report |

The sessions below will focus on more generic study-skills workshops relevant to key milestones in the dissertation/critical literature review.

| Tutorials/webinars – All sessions will be run at 17:00hrs UK time | |

| Tuesday 19th October 2021 | Starting out and options |

| Tuesday 7th December 2021 | Moving forward – planning and starting to write |

| Tuesday 5th April 2022 | Developing critical argument |

| Tuesday 2nd August 2022 | Bringing it all together for submission |

Please note that occasionally it may be necessary to change times at short notice. Therefore it is important that students check their university emails and the Announcements section in Blackboard and the Dissertation discussion board found in Blackboard/MPH Programme Community/Discussion Boards.

MPH vs. MRes

To complete the requirements for an MPH or MRes, students need to accomplish a pass across 180 credits. The balance between dissertation and course units required is shown below:

| Number of taught units | Dissertation | Total credits | Word count | |

| MPH | 8 (=120 credits) | 60 credits | 180 credits | 10,000 to 15,000 |

| MRes | 6 (=90 credits) | 90 credits | 15,000 to 20,000 |

Intended Learning Outcomes

| Category of outcome | Students should be able to: |

| A. Knowledge and understanding | A1 Describe in detail a specific context, setting and/or problem and establish a coherent research-related question that forms the foundation of the written dissertation report/manuscript |

| B. Intellectual skills | B1 Construct a meaningful synthesis and critical interpretation of existing and new information, obtained as part of the dissertation process |

| C. Practical skills | C1 Apply appropriate methodology to obtain the data or information necessary to address the research question

C2 Use a justified methodology to analyse the data and/or information collected |

| D. Transferable skills and personal qualities | D1 Demonstrate the ability to be a reflective and self-directed learner, to accomplish a substantial piece of academic work |

What is a master’s dissertation?

A master’s dissertation is a focused, critical and reflective body of writing that seeks to add to the understanding and knowledge of a particular problem or question. It is an opportunity for you to expand your knowledge and expertise in an area of study. To pass your dissertation, you will need to show your ability to provide in-depth, critical and reflective thinking, relevant to the focus of the dissertation. It is your own work and not that of your supervisor. The role of your supervisor is to support your learning experience but not to do the thinking for you. Appendix X shows an example of a marking framework currently used to assess dissertations.

In the UK, the requirements for a master’s degree are defined by the Quality Assurance Higher Education Agency. The following insert includes those sections of particular relevance to your dissertation. You will see the emphasis on the need to demonstrate critical application and reflection.

| Master’s degrees are awarded to students who have demonstrated: | |

| (a) | A systematic understanding of knowledge, and a critical awareness of current problems and/or new insights, much of which is at, or informed by, the forefront of their academic discipline, field of study or area of professional practice |

| (b) | comprehensive understanding of techniques applicable to their own research or advanced scholarship |

| (c) | originality in the application of knowledge, together with a practical understanding of how established techniques of research and enquiry are used to create and interpret knowledge in the discipline |

| (d) | conceptual understanding that enables the student:

|

| Typically, holders of the qualification will be able to: | |

| (e) | deal with complex issues both systematically and creatively, make sound judgements in the absence of complete data, and communicate their conclusions clearly to specialist and non-specialist audiences |

| (f) | demonstrate self-direction and originality in tackling and solving problems, and act autonomously in planning and implementing tasks at a professional or equivalent level |

| (g) | continue to advance their knowledge and understanding, and to develop new skills to a high level. |

| And holders will have: | |

| (h) | the qualities and transferable skills necessary for employment requiring:

|

| HEA. Part A: Setting and maintaining threshold academic standards. Chapter A1: The national level http://www.qaa.ac.uk Accessed June 2012. | |

Types of Dissertations

The MPH/MRes programme aims to address the needs of public health professionals now and in the future. Reflecting this, along with student feedback, the dissertation unit includes a number of different approaches with regards to the type of dissertation and methodology. Further guidance on these is given in the Appendices. The different approaches (sometimes referred to as options or framework) are:

| Primary research project

Systematic review (see note below) Analysis of existing data (quantitative or qualitative) Qualitative/theoretical project N.B the MPH refers to an adapted systematic review, rather than full review. See specific information in the Appendices |

Note that all of the options are suitable for both quantitative and qualitative methods. Students are encouraged to read the detail given in the Appendices for all of the possible options, as some of the information will be helpful for more than one. Each option is marked using the same grading categories, and one is not easier than another (although of course, students differ in terms of their abilities, and like any assignment, will find some easier to complete than others).

Marking Framework

Appendix X provides information regarding the marking framework and guidelines. This is exactly as what will be given to the examiners. At the beginning of the unit it is helpful for students to understand the marking criteria and allocation of marks for a completed dissertation. This will enable students to develop a better sense and understanding of what they need to produce in order to pass, and achieve a higher mark. The Appendices include information about the criteria associated with different marking bands, and an example of a specific marking sheet. The mark sheet will how the total marks available for a dissertation are divided across a number of different categories. This information applies to both MPH and MRes students.

External partner project opportunities

Each year there are a limited number of opportunities for MPH or MRes students to undertake a dissertation project with either a researcher based in the team at The University of Manchester, or one of our external partners.

The partner project initiative is coordinated by Greg Williams (greg.williams@manchester.ac.uk) and Christine Greenhalgh (christine.greenhalgh@manchester.ac.uk) If you are interested in working with a researcher, or an external partner for your dissertation then please contact both of them at the earliest opportunity. There are only a limited number of places available each year and these cannot be guaranteed.

Researchers or external partners may be able to provide you with research ideas, data and/or access to expert practitioners. You will still be allocated a University of Manchester supervisor to oversee your dissertation and must follow all guidance as outlined in this handbook in addition to the standard university regulations as part of your programme as a whole.

To give you an example of the kind of opportunities that may be available, our external partners in the year 2020-21 have been:

- Greater Manchester Health and Social Care Partnership / Manchester University NHS Foundation Trust

- Lancashire Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust

- Public Health England

- The TRUUD Consortium

It is the intention for additional partners, including international partnerships to be added in due course. Information on these will be available through the usual student communications. We are also happy to look for potential partnerships based on your interests/skills, where we may already have an ongoing relationship.

Partnership projects – things to consider

It is worth considering that depending on the partner and the project proposal, some additional, potentially time-consuming, requirements may need to be addressed. For instance, a data sharing agreement, data storage needs, and/or ethical approvals. While none of these issues would preclude you from undertaking a project, they may mean that such a project is not right for you.

Although the partnership projects can be a great opportunity for you to make external connections and produce work that is of value beyond your dissertation, it is important to remember that your dissertation is the number one priority. This means that any unforeseen circumstances, such as delays in data collection, must be thought about in your planning and cannot be used as mitigating circumstances. Remember that organisations may have different competing priorities to yours and timescales might end up being different to those initially agreed. Therefore students need to ensure that they will be able to adopt their initial ideas into a suitable dissertation, even if changes in the partnership relationship and priorities change over this period. The academic supervisor can help guide and suggest possible solutions such as recommending a change in the format of the dissertation to accommodate any challenges and necessary changes

Please make contact with Greg and Christine to discuss this further.

Research Ethics and Governance

ALL dissertation students and their supervisors need to adhere to correct research governance, and research ethics. Detailed information is given on the University website at University ethical approval | The University of Manchester

Students and their supervisors are responsible for ensuring that the correct governance (including ethics) approval has been secured and then adhered to as research is carried out. Some of these requirements are not just for students collecting new data (primary research), but apply to analysis of existing data too. Even a research grant proposal option would need a section dedicated to this topic.

Three sources for external information include:

Information Commissioner’s Office

Medical Research Council information on good research practice

Research Ethics Online Decision Tool

All students need to use the online ethics decision tool to determine if their work will require ethical approval. A screenshot of the final decision from this decision tool (it does not produce a document) needs to be taken and included in an Appendix in the submitted dissertation: – UREC Decision Tool

Students also need to submit evidence that they sought permission to access and use any data and information from within a specific organisation, even if formal ethical approval is not required. This applies if the information is not in the public domain (but see the sections above if it is to do with NHS or equivalent data, or data considered to be ‘sensitive’ in nature) . This needs to be from a Director / senior manager, on letter headed paper, signed and sent as a PDF to the students’ academic supervisor. It is good practice for a copy of this to be included in an Appendix in their dissertation.

The key message is – all students need to ensure they understand and adhere to the international principles of good research conduct. Therefore students need to read the information on ethics and governance on the main university webpage, and then complete the UREC Decision Tool.

| University ethical approval/governance |

| UREC Decision Tool |

| Further clarification with regards to the MPH/MRes is available from:

Division Lead Ethics Signatory: Christine Greenhalgh |

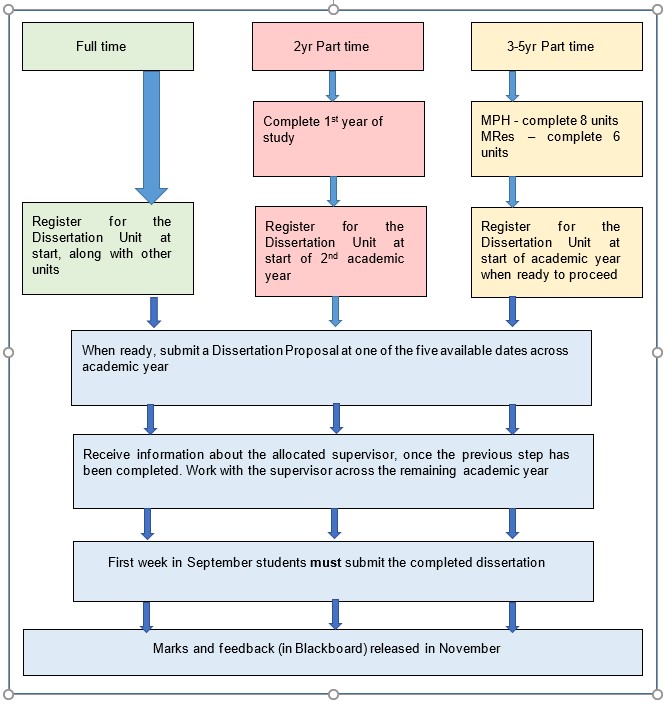

When must students start the dissertation unit?

- Full-time students start along with the individual taught units, towards the beginning of the academic year. Students often spend a few weeks settling into the programme, before submitting ideas for the dissertation (see Section Submitting Ideas).

- Part-time students on the 2 year route start in their second year.

- Part-time students on the 3-5 year route will normally start their dissertation after successful completion of their taught units (8 units for MPH and 6 units for MRes).

Deadline for submitting the completed dissertation

All students must submit their completed dissertation in the first week in September at the end of the academic year within which they registered to start the dissertation unit. Note that the academic year runs from September to September. Therefore, full time and part time students starting the dissertation in the academic year September 21/22 must meet the final submission date of 12:00 noon BST on Monday the 05th of September 2022.

Process Flow Chart

The following figure shows the route through the dissertation year. Note that once a student registers to start the dissertation unit, they must submit by the forthcoming September.

Do not leave it too late

|

Keep in mind that once a student has formally registered for the dissertation unit, they have to submit the completed dissertation by the Sept at the end of the academic year. In other words, students are strongly encouraged not to leave it too long from registering at the start of the academic year, to then actually working on the dissertation and with support from their supervisor. |

Submitting your ideas

Students need to complete a short proposal form to indicate the title and a very brief outline of what they will be focusing on. There are five fixed dates when students can submit the proposal form. Proposals will not be processed between these dates. These dates reflect the academic timetable, and help account for assessment times and holidays. However, make sure you plan as much time as possible for working on your actual dissertation. The earlier you start in the academic year, the better.

Proposal Form Submission Dates

The following table shows the dates available for students to submit their dissertation proposal, explained above.

| Proposal submission dates | |

| One | 27th October 2021 |

| Two | 15th December 2021 |

| Three | 31st January 2022 |

| Four | 7th March 2022 |

| Five | 2nd May 2022 last opportunity! |

Academic Supervision

Students will be allocated an academic supervisor soon after completing the process above. Students then need to make contact with, and introduce themselves to their allocated supervisor.

Role of the Supervisor

The role of the supervisor is to support a student’s academic development. Remember the dissertation is the work of the student and not that of the supervisor. Students will have different needs for support and guidance. Some of the areas a supervisor might help with include:

- Helping students to develop a meaningful time plan for the months ahead

- Supporting the development of the structure of the dissertation in terms of sections and themes that it includes

- Giving constructive feedback on sections of written work/preliminary drafts. This includes feedback on the general style of writing, appropriate use of references, and the depth of critique/appraisal that the work contains and relevance to the original aims and objectives of the work

In addition:

- Supervisors aim to give feedback to students within 2 weeks of submitting drafts. As a result, it is important that students plan their time and allow for the return time for feedback on their work

- Please do not expect supervisors to be able to give feedback very close to the submission date. Also, this would not provide enough time for students to respond to their comments

- Supervisors are expected to provide around 20 hours of support for dissertation students. This includes reviewing student drafts and individual meetings.

N.B Supervisors are asked to let students know if they will be taking annual leave in August/early September. This will help students plan their work and when supervisory support can be provided. It is a good idea for students to clarify this with their supervisor.

Maximising Supervision

Students are encouraged to maximise the opportunities for support from their academic supervisor. A few suggestions to facilitate this include:-

- Send supervisors an email as a way of introduction, a time plan, and any immediate concerns/support needs

- Identify specific queries or questions as a way of preparing for a discussion/meeting with the supervisor

- Have a good awareness of the marking template used to assess the final written work (see end of document). Knowing the assessment criteria helps guide a student’s work and supervisory discussion

- Make the supervisor aware of any difficulties affecting the ability to study. Students do not need to specify the detail, but enough to help the supervisor signpost the student to other sources of support. At the same time, it is helpful for any students with issues impacting on their studies, to let mph.admin@manchester.ac.uk know.

- Raise any issues associated with supervision by contacting Roger.Harrison@Manchester.ac.uk or Andrew.Jones@Manchester.ac.uk

Additional support

All students are encouraged to utilise the My Learning Essentials packages provided through the online UoM library. There are also helpful resources provided in the MPH Programme Community relevant to both the dissertation and the Critical Literature Review.

Milestones

Students are strongly encouraged to draft and share a plan for the academic year with their supervisor. This will help them to develop a realistic understanding of the amount of time required to achieve key milestones over the months ahead. Working back from the final submission date is a good way to appreciate what needs to be done, to meet the final submission date.

Always let mph.admin@manchester.ac.uk and your supervisor know of issues impeding your studies so that they can make a record and provide support.

Word Counts

The dissertation has a word count limit, specified as a range. This differs for the MPH and the MRes as shown below:-

| Programme | Word count range |

| MPH Dissertation (60 credits) | 10,000 to 15,000 |

| MRes Dissertation (90 credits) | 15,000 to 20,000 |

- As a general guide, the Abstract needs to be around 300 words

- The student needs to indicate the final word count, at the top of the cover (first page) page the dissertation. This will be based on the inclusions and exclusions as described below. Breaching the upper word limit can incur penalties and marks can be deducted

Inclusions, Exclusions & Penalties

Detailed information about word counts, what is and is not included, marking penalties and the marking framework used for assessment, is given in the Appendices.

Dealing with your own publications/presentations

Students are encouraged to disseminate work associated with their academic studies, including the dissertation. This can include publications in printed and online journals, blogs, textbooks and conference presentations. However, steps need to be taken to avoid academic malpractice. Before submitting a dissertation, it is important for students to reference any publication (or work formally accepted for publication) that directly relates to the dissertation. This means students will need to reference their own published/presented work, if aspects of this are included in the dissertation. Failing to do so puts the student at risk of academic malpractice, including plagiarism. Furthermore, students must not directly copy and use the same material in their dissertation that is presented in a publication

Use of appendices in the dissertation

Information in the appendices is not marked by the examiner and is not included in the word count. Therefore, whatever you include in the appendices must not form a considerable component of the dissertation itself and no marks are attached to these.

However, for a dissertation, it can be of general interest to include items that are indirectly related to the main body of the dissertation. For example:

- A copy of a questionnaire created by the student (but this would not be marked)

- A copy of the complete data analysis output (such as from Stata/SPSS) (but this would not be marked)

- A copy of the full search strategy as used in Ovid, Pubmed, etc. (but this would not be marked). However, students will still need to evidence of the results of your actual search in the main part of the dissertation. This is to show how successful your search was, the type of information/studies retrieved, and the number. This is especially important when conducting a systematic review, but applicable to other dissertation formats too.

As the appendices are not marked, students must ensure that information central to the dissertation is included in the main part of the written sections. Therefore, with regard to the three examples in the list above, more specific detail and explanation might be better placed in the main part of the dissertation, otherwise it would not be included in the formal marks.

Formatting/layout

The University has a number of important requirements regarding the way in which the written dissertation is laid out. For the main text, double or 1.5 spacing with a minimum font size of 12 must be used; single-spacing may be used for quotations, footnotes and references. A number of preliminary pages need to be included too, specific to the programme of study..

Adhering to a clear and consistent presentation format can facilitate the marking process and students can lose valuable marks if their presentation is poor. The examples of previous dissertations, included in Blackboard, can help direct students to appropriate styles to use.

Further guidance for the presentation of dissertations is available here.

About the author

Students are encouraged to include a short section in the preliminary section called ‘About the author’ – writing a couple of paragraphs about the student’s background/current role, helps the marker see a bigger picture. However, it does not influence the marks awarded/adherence to the marking framework

Referencing

The use of referencing will be assessed by the examiners. On this programme, the preferred referencing style is Harvard. However, Vancouver is acceptable. Students must correctly reference their work. Poor approaches to referencing can suggest academic malpractice. Guidance can be found on academic writing and referencing in the Study Skills course within the MPH Programme Community space in Blackboard and from the University My Learning Essentials.

It is essential that students develop the referencing they write their dissertation. There are a number of free online and cloud-based programmes to facilitate this process (including Endnote and Mendeley). Please ensure that the final reference list is produced correctly, especially if you are using an automated process, through Endnote/Mendeley for example. Sometimes software can cause final problems with this as part of the upload process. Therefore producing a final .PDF document might be preferable.

Deadline for submitting the completed dissertation

Students need to submit one electronic copy of the dissertation through Blackboard (similar to a course unit assignment). Printed copies of the dissertation are not needed.

MPH and MRes students need to submit the electronic copy on or before the 12:00 noon BST on Monday the 05th of September 2022. Students can submit earlier than this, but they will not get their mark any earlier.

|

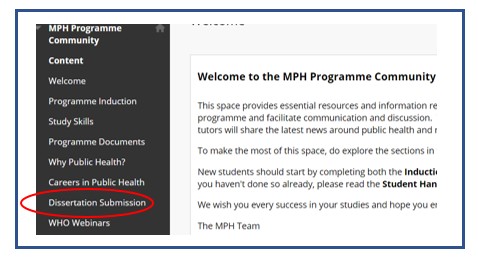

Where to submit

The place to submit the electronic copy is in Blackboard in the MPH Programme Community space under My Communities. This is indicated in the diagram below:-

What next?

All students are encouraged to consider ways to disseminate aspects of their work. This can include a blog post, presentation, or more formal dissemination such as publication in an academic journal. This can also enhance a student’s CV and contribute to their career development. A publication could take on any number of formats including:

- A commentary/editorial

- A study report

- A case report

- A letter to the editor

Publishing/presenting your work

Students can discuss potential publication with Roger Harrison/Andrew Jones. They will have ideas about the suitability of your work, the relevant journals, and what aspects to focus on. Students can also ask if their supervisor could help with this work, although that is outside of the main supervision role. Students are asked to acknowledge in any dissemination that the work was associated with the MPH/MRes. We are always keen to know what/how students do in relation to their MPH/MRes. Therefore, please send information regarding any successful publications, even if that occurred after graduation, to roger.harrison@manchester.ac.uk Further, information on any career progression or grant funding, that was influenced by the MPH/MRes, is always good to hear about.

Appendix I – Research Grant Proposal

This option is likely to appeal to students who have identified the need for a particular area of research or those keen to develop a research project after completing their postgraduate degree. It may also be helpful for students looking to start a research focused course of study in the future (such as a PhD). Some aspects of this option will reflect the requirements for formal proposals such as those to the Medical Research Council (MRC) or the Economic & Social Research Council (ESRC). Remember that you will be assessed against the marking framework included as an appendix in this handbook. Therefore, your dissertation will need to contain appropriate critical appraisal and reflective thinking at appropriate sections in the dissertation.

The course units Practical Statistics for Population Health, Fundamentals of Epidemiology, Evidence Based Practice, Qualitative Research Methods and Economic Evaluation in Healthcare may be of particular relevance to this option.

This can apply to Quantitative AND Qualitative methodology and likely to consist of three broad sections, broken down into individual chapters.

A) Lay Abstract. The Research Grant Proposal will need to have a Lay Abstract in replacement of a more academic/scientific abstract. The suggested word count for abstracts is 300 words. Resources for examples are included here:

(a) How to Write a Lay Summary | DCC

(b) How to write a lay summary – research grants | BHF

B) Case for support. This section needs to show:

i) Why does this particular research need to be done?

ii) Why should resources be dedicated to this topic and what gaps in knowledge does the research seek to address?

iii) How might it lead to an improvement in a particular setting/context/population?

You will clearly formulate the problem, setting it in context of scientific and/or theoretical debates. You need to show how it is relevant to trying to improve the health of a particular group of people or locality. This section will include a detailed critique of existing literature relating to the topic and bring in other information to highlight the case for support. You will acknowledge and critique existing studies or data sources and explain the problems with these – in other words, why more research is needed. It is important to reflect on the implications of the proposed research in terms of future healthcare policy/planning or interventions and how it might benefit potential users of your findings. Thus you could include at some point in the dissertation a clear dissemination policy of your findings.

C) Research/study methods. The detailed study design must be directly related to your stated primary and secondary objectives and capable of answering the proposed research question. Whilst you are not asked to go on and do the actual study, the proposal must be related to current circumstances and existing evidence – it must be a study design that could actually be carried out in practice. You will give a clear rationale for the particular elements of the research project, using appropriate references to support specific parts of your study design. For example, your methods of sampling (if relevant) and evidence to support the sample size for the project need to be clearly justified. Similarly you need to justify your choice of data collection methods/measurement tools, and what can be expected in terms of response rates. Part of the study design will include an analysis plan of your collected data. It is not sufficient to just say that “methods suitable for continuous data will be used” for example – you need to give a detailed plan and again support your methods.

- A section on resources/costings is required. Here you need to provide information on the direct costs to carry out the research project. For example, how many community workers will interview people and how much will it cost to employ them? This section must be realistic, set in a particular context/country and where possible, supported with evidence. This will coincide with a detailed time plan which can be helpful to present as a Gantt chart.

- All research needs to follow accepted ethical principles such as the Declaration of Helsinki and research governance. Whilst these may vary across different countries, remember that your final postgraduate award (if successful) is from the University of Manchester – as such you would be expected to show your understanding and application of research ethics and governance expected from research conducted in the United Kingdom and apply this as appropriate to your own setting. This will include an assessment of risks to different stakeholders and how you have tried to minimise any risks, including contingency plans, in your research design.

D) Discussion. The discussion section is one of the most important parts of any dissertation. Here you need to reflect on the relevance/importance of your research question and of your proposed research design. This can bring in some of the wider literature/evidence to develop arguments to highlight the strengths and weaknesses of your proposed research. You can discuss and reflect on some aspects of the study design, including a critique of your methods, and show how you have tried to use rigorous methods for your research that reflect the body of existing knowledge in that area. Research rarely goes to plan and you can show how you have considered some of the potential difficulties in completing the research and how you have tried to overcome these in your proposal. Whilst you will not have any actual findings to discuss, you can postulate what these might be and the implications of a positive or null-finding from your research in terms of service delivery/health policy for example.

Other sections are likely to include references, appendices etc.

Marking Framework

Please note that the Marking Framework for this option includes one difference to that used for all the other dissertations: because there will not be any ‘results’, the marks allocated for this on other dissertation frameworks, have been added to the criteria sections ‘Design of the study’ and ‘Discussion’.

Bibliography.

Chapman, S & Mcneill, P. (2003). Research Methods. London. Routledge.

Bowling, A. (2011). Research Methods in Health: investigating health and health services. Buckingham. Open University Press.

Crosby R. DiClemente RJ & Salazar LF. (2006). Research Methods in Health Promotion. San Francisco. Jossey-Bass.

Ulin, P, Robinson ET & Tolley EE. (2004). Qualitative Methods in Public Health: A Field Guide for Applied Research. San Francisco. Jossey-Bass.

Links:

How to Write a Research Proposal

Medical Research Council – guidance on grant applications

The Economic & Social Research Council

How to Write a Research Proposal

Appendix II – A new research study/project

The dissertation provides an opportunity for MPH and MRes students to collect new, primary data (i.e. conduct a research study/project). This is of particular interest for students who intend to pursue a research-focused career, or one with a strong element of this within. The research study can be based on any suitable methodology but one which is agreed by the student’s supervisor

Embarking on a new research study/project can be a practically challenging task. All students need to do background work to ensure that the study can be completed within the timescales of the dissertation.

Students are responsible for establishing their own research study. However, this can be part of the partnerships, as discussed earlier in this handbook, or students can join an existing research programme that is running elsewhere.

Identifying and if relevant, gaining research ethical approval is a key criteria, and students will not be able to proceed unless this has been secured where needed. This will include ethical approval from the University of Manchester, in addition to that which might be needed outside of the university setting (e.g. for research within the context of the NHS).

Students wishing to pursue a primary research project will need to discuss their ideas and approach with Greg.Williams@Manchester or Christine.Greenhalgh@Manchester.ac.uk in advance.

Additional guidance about the suitable research design, and structure for the dissertation can be gleaned from reading other sections in this handbook.

Appendix III – Quantitative Analysis of Existing Data

This option takes the format of a quantitative research project. It provides an opportunity for students to collect new, primary data (i.e. conduct a research study) or to analyse data from an existing data set to which they can access. For primary data you are likely to require ethics approval. For secondary data you must demonstrate permission to access and use the data for the purposes of your dissertation with a formal letter from the person/organisation responsible for the data. You will also need to provide assurance that any original consent attached to the data does not preclude you from using the data for your dissertation.

Sources of data are likely to include routine datasets/surveillance information, such as those accessed from the World Health Organisation (WHO) or national surveys such as the Health Survey for England. In some circumstances, you might have access to more locally based sources of data, such as routine statistics from a health care provider. It is also possible to use data from an established research project that you have been involved with.

The course units Practical Statistics for Population Health, and Fundamentals of Epidemiology, will be of particular relevance to this option.

A quantitative research report for the dissertation will include the following sections. These are usually presented in the form of individual chapters:

- Introduction, Background & Critical Review of Existing Literature. These sections will cover similar issues/areas to those highlighted in the Case for Support in the option of Research Grant Proposal, on the previous page.

- Methods & Study Design. You will need to provide a detailed plan, and justification for your proposed methods of analysis. In addition, you will need to provide a detailed description of the data set, including how the information was obtained, over what time period, using what methods, who was invited to participate and who actually took part. You will also need to be clear about the aims of the main data set/research project, AND of your specific aims that you are seeking to address in the dissertation. This will be followed by your proposal to answer those questions yourself using all or part of the dataset. In a way, you might be carrying out a study nested within a much larger information/research project. At some point in your dissertation you will need to give attention to the integrity of the data, and how reliable it might be.

- Analysis & Results. This will form a key part of your dissertation, along with the other sections. Before starting the analysis, you will need to spend time exploring and examining the data. You will need to check and report on data quality and any management required to present them in a workable format for your dissertation. Do not underestimate the time involved in the data cleaning and preparation stage. In the analysis you will need to justify any deviances to your original plan and be clear about any assumptions that you make. In presenting your results, think about the most effective ways to present and communicate your findings. Remember that you want to capture key findings from the study in a clear and meaningful way; otherwise the reader will find it difficult to identify what you found. However, there is a balance to be had in terms of the number of tables, charts and graphs. Focus on presenting what the reader needs to know and understand in relation to the original objectives. A key skill is in knowing what and how much needs to be presented by way of analysis output and results.

- Discussion The discussion section is one of the most important parts of any dissertation. Here you will reflect on the relevance/importance of your research question, the quality of your research findings, and set these into the current context of existing knowledge. You can bring in some of the wider literature/evidence to develop arguments to highlight the internal and external generalisability or strengths and weaknesses of your research and show what value can be placed on your actual findings. It is important to discuss the value of the existing data source and to consider alternative / superior ways to answer your research question in future. The discussion section usually includes consideration of the implications of your findings, particularly to health policy and practice. In other words, what recommendations might arise from your work. It is not uncommon to find dissertations and academic papers finishing with the phrase “more research is required” – this obvious statement conveys little information to the reader about what you actually know about the subject. If questions remain unanswered then provide some direction in terms of how they might be answered.

Other sections are likely to include references, appendices etc.

Bibliography

Bland M. (2000). An Introduction to Medical Statistics. Oxford. OUP. Statistics At Square One.

Bowling, A. (2011). Research Methods in Health: investigating health and health services. Buckingham. Open University Press.

Chapman, S & Mcneill, P. (2003). Research Methods. London. Routledge.

Links

Research Methods Knowledge Base

Guidelines for Presenting Quantitative Data

Appendix IV – Full or Adapted Systematic Review

This can be of quantitative OR qualitative data

There are two core differences between the requirements for MPH and MRes students:

- MPH students are not expected to complete a full systematic search and review of the literature, largely because they have less time than MRes students. An adapted review refers to ways to produce a manageable amount of references (or potential references) for a single student to deal with in a less amount of time than MRes students

- MRes students are usually expected to complete a full systematic review.

Rationale for the ‘adapted’ approach

The option of completing an adapted systematic review provides an opportunity for MPH students to develop their skills in systematically collating, assessing and summarising existing sources of evidence. The amount of work involved can be influenced by the number of studies potentially eligible if it were a full, in-depth review (e.g. Cochrane Collaboration style). Consequently, for the purposes of this dissertation, MPH students can limit the number of studies in their review (see below).

The course units Practical Statistics for Population Health, Fundamentals of Epidemiology and Evidence Based Practice will be of particular relevance to this option.

Introduction/background: This is similar to the Case for Support described earlier in the Grant Proposal option.

Study design/methods including: You need to develop a suitable review methodology appropriate to your research question. The structure of the review is then likely to include:

- Clearly defined research question

- Definition of intervention

- Criteria for inclusion/exclusion of studies

- Definition of study populations

- Primary and secondary outcomes for the review

- Methods of analysis/summarising data

- Methods for assessing study quality

- Search strategy & sources of literature/information

Analysis / synthesis of results. Note that you are not expected to complete a meta-analysis for the dissertation though you can include one if appropriate.

Results including:

- Flow chart of search process/included & excluded studies

- Summary of data extraction

- Summary of included studies

- Assessment of methodological quality

- Summary of treatment effects

Discussion: this is likely to cover some of the areas/issues described in the proceeding dissertation option “Quantitative Research Report”

Other sections are likely to include conclusion, references, appendices etc.

Dealing with too many or too few studies (MPH students)

Good quality search strategies for some research questions can identify hundreds, sometimes thousands of potentially eligible studies to be reviewed. MPH students are unlikely to have sufficient time to suitably deal with this. Consequently, it is possible to incorporate sensible approaches within the study design to limit the number of studies for the dissertation. For example:-

- Limiting the range of time (years) that publications will be considered eligible. Such as running a search from 2016-2021, as opposed to 1980-2021 (or whatever wider range would be used for a full and complete review).

- Restricting to a specific country/region (such as UK, or sub-Saharan Africa etc)

- Limiting to a specific population (e.g. just women, or by a specific age group).

The use of these approaches should be justified in terms of your review question. For example, an appropriate reason for date restriction could be to assess new evidence published since a Cochrane review or guideline, restricting to a specific country or group of countries could be justified by population demographics or healthcare structure and access. If you use one of these approaches then it needs to be clearly stated in the methods, results and discussion section.

In some cases, you might find less than a handful of potentially eligible studies for your review or none at all. This does not rule out conducting a systematic review for your dissertation though it can make it more challenging.

Working with a second reviewer (MPH and MRes)

You may know that a high quality systematic review is usually carried out by at least two reviewers. The main reason for this is to carry out independent screening and data extraction, as a way of confirming results and reducing selection bias.

Some students might be in a position to ‘recruit’ someone to act as a second reviewer. This would be necessary if the student wanted to publish their work. It can also provide an opportunity to enhance a student’s research and facilitation/team work skills. If this approach is taken, it is essential that this is transparent across the dissertation, and that the student is able to clearly identify what is their own academic work. In other words, whilst the second reviewer is largely carrying out task-based functions, the core of the dissertation itself needs to be the work of the student.

Bibliography

Akobeng, A.K. (2005) Understanding systematic reviews and meta-analysis, Arch.Dis.Child, vol. 90, no.8, pp.845-848 [online].

Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions http://www.cochrane.org/training/cochrane–handbook/

Centre for Reviews and Dissemination. CRD’s guidance for undertaking reviews in health care. http://www.york.ac.uk/inst/crd/pdf/Systematic_Reviews.pdf

Greenhalgh, T. (1997) Papers that summarise other papers (systematic reviews and meta-analyses), BMJ, vol. 315, no. 7109, 672-675 [online]

Appendix V – Academic Public Health Report

Many public health professionals will be expected to produce public health reports in relation to a particular issue/subject. On the MPH/MRes, these are prefixed as ‘Academic’ Public Health Reports, to ensure that students appreciate the need to apply scientific and evidence-based rigour, with academic critical and reflective argument throughout, and clear justification for approaches considered. This may differ to less detailed organisational reports at times. The course units Practical Statistics for Population Health, Fundamentals of Epidemiology and Evidence Based Practice will be of value for this option, but not restrictive to just these.

The format for an academic public health report will vary according to the topic/focus and primary objectives. The following acts as a general guide:

Aims: students need to demonstrate their appropriate understanding, application and critical reflection of theories/models and existing knowledge to inform a specific public health question, often focused on a particular locality/setting and to consider future interventions and policy direction.

Types of Reports: In most (but not all) situations, an academic public health report will be used to address certain aspects associated with an existing or pending problem in a specific area or context. The types of public health reports likely to be presented for a dissertation include:

- Health needs assessment / health impact assessment

- An audit / evaluation of service delivery

- An outbreak report

- Option appraisal

- Policy evaluation

Structure & objectives: The specific structure and objectives of the academic report will be influenced by its focus / initial public health question. But in all academic public health reports, students need to demonstrate their ability to appropriately use and understand the main skills and principles that have been covered across the MPH course. Students are encouraged to critically present and reflect on any existing or proposed policy relevant to the focus of the report. Thus, students need to be able to challenge the status quo or proposed policy direction set by organisations, local, national or international bodies & government.

The content of an academic public health report is likely to cover material from the following sections:

Burden

- To clearly identify, describe and present a public health issue, often focused on a particular locality / setting or population

- To present an analysis of the issue

- To use available data sources where possible to describe the actual possible burden or impact of the issue, including historical, current and future impact and to set this in relation to other key population characteristics and health issues. Data and information need to be presented in a meaningful way and appropriate to the focus of the report

- Recognising that there might be limited information on the specific issue in this setting, students need to find other sources of data to inform and estimate the possible circumstances. Rarely does a locally based public health problem arise without any suggestive or interpretative information from elsewhere which can then be used to inform the local picture.

Context

- To set the issue in a relevant policy context, be it a specific local, national or international setting.

- To critically review literature relevant to the focus of your public health report. This can include critical reflection of evidence relating to epidemiology, interventions and policy. You will need to describe how you sourced or searched for evidence and information, why, and what methods you used to critically appraise the information.

- To identify and examine possible policy drivers and what or how these could influence the current/future situation; in some reports this may require the use of a formal policy review framework.

Interventions & recommendations

- The report must include a section examining possible interventions, changes to practice, or policy directions, which need to reflect on the principles of evidence based practice. The possible impact/expected change from these recommendations needs to be explored in relation to the specific issue.

- All interventions and recommendations need to be clearly linked to earlier sections in the report and you need to show what gaps/problems/ or issues, identified earlier, that they aim to resolve.

- To consider and propose relevant surveillance/monitoring or research to meet gaps you have identified and show how this could then be used to address / inform the issue.

Other sections are likely to include conclusion, references, appendices etc.

Writing style

A number of different styles or frameworks can be used to present your academic public health report. Typically your work needs to follow a structured approach, making use of clearly labelled sections, headings and sub-headings. These will help you signpost the reader to various parts of the report as the work progresses, showing how different aspects are linked.

- Academic public health reports need to finish with a clear summary of the main features/points in your report and recommendations must clearly reflect the main body of the report.

- Students are not expected to carry out a full systematic review of the existing literature. But they do need to carry out a sensible and robust way to provide evidence on the burden, context, and possibly evidence of interventions, amongst other things. A description of the approach to source relevant literature needs to be included in the main part of the dissertation, and often this includes a summary of the search strategy from an online database.

- You need to explain and critically reflect on any methods used throughout your report. This includes those relevant to data/information seeking, appraisal, impact and review. Thus highlighting the relevance and strength of the information, to inform the specific issue.

- Think carefully about the structure and order of your report. There needs to be a common thread throughout the report and all sections need to be clearly linked to the initial issue presented.

- Avoid over use of bullet points and use complete sentences to present most of your work. Use meaningful charts, tables and figures – but there needs to be a clear reason for including these and a link to relevant text.

- If you are including an executive summary then there is no need to write an abstract as they are likely to contain very similar information. However, it is a requirement that dissertations have an abstract. Therefore we suggest that you simply use the executive summary for the abstract, but make sure that the main heading for that page is “Abstract” and then a subheading “Executive Summary”.

Bibliography

Bowling, A. (2011). Research Methods in Health: investigating health and health services. Buckingham. Open University Press.

Chapman, S & Mcneill, P. (2003). Research Methods. London. Routledge.

Crosby R. DiClemente RJ & Salazar LF. (2006). Research Methods in Health Promotion. San Francisco. Jossey-Bass.

Ulin, P, Robinson ET & Tolley EE. (2004). Qualitative Methods in Public Health: A Field Guide for Applied Research. San Francisco. Jossey-Bass.

Appendix VI – Outbreak Report

To be read in addition to the guidance on writing an Academic Public Health Report, in the previous pages. This option might be of interest to students working in a public health setting with an interest in examining a particular event or outbreak. A common approach would take:-

Introduction, background & setting: aims of the report; contextual information. Population profiles, surveillance data and a description of the site, area or facility under investigation.

Literature review including a description and critique of previous outbreaks

Outbreak methods:

- How was the outbreak discovered/reported?

- Steps taken to confirm it?

- What was known then?

- Why the investigation was undertaken?

- What were the objectives?

- Management of the outbreak?

- Who assisted in the investigation?

- What control measures were taken?

Results

Discussion including: a critique of the outbreak investigation and methods; comparisons with similar outbreaks and previous studies; relevance of the results in the local context and other settings; recommendations and justification for any action needed.

Other sections are likely to include conclusion, references, appendices etc.

Bibliography

Bowling, A. (2011). Research Methods in Health: investigating health and health services. Buckingham. Open University Press.

Buehler JW et al. (2004) Framework for Evaluating Public Health Surveillance Systems for Early Detection of Outbreaks. MMRW. 53 (RR050; 1-11. http://www.cdc.gov/Mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr5305a1.htm

Chapman, S & Mcneill, P. (2003). Research Methods. London. Routledge.

Crosby R. DiClemente RJ & Salazar LF. (2006). Research Methods in Health Promotion. San Francisco. Jossey-Bass.

Ulin, P, Robinson ET & Tolley EE. (2004). Qualitative Methods in Public Health: A Field Guide for Applied Research. San Francisco. Jossey-Bass.

Ungchusak K, Iamsirithaworn S. “Principles of Outbreak Investigation”. Chpt 6.4. In Oxford Textbook of Public Health. Volume 2. (2009).

Appendix VII – Qualitative/Theoretical Study

This option will appeal to students who have a particular interest in qualitative methods and research. It is likely that they will have taken the unit Qualitative Research Methods and encouraged to refer to the course curriculum to help develop their ideas. Types of approaches for this dissertation option include:

Metasynthesis: Students should choose a topic that has been previously researched via a number of published qualitative research studies and produce a metasynthesis.

Qualitative study using available data: Students might already have access to existing data. Or may want to make use of available data sources such as, ESDS Qualidata (http://www.esds.ac.uk/qualidata/about/introduction.asp) or the UK Data Service (https://www.ukdataservice.ac.uk/get-data/about.aspx)

Qualitative study involving primary data collection: Students will need to consider whether they will need ethical approval and the time taken to achieve both this and data collection. An early start date for this option is strongly recommended.

A theoretical review: Students would choose a topic of interest and address some theoretical questions by reviewing previous theoretical and empirical (where relevant) work. Examples of topics that could be addressed in this way include:

- The social/ cultural construction of risk in relation to a number of health issues.

- The conceptualisation/ measurement of disability in relation to meeting health and social needs.

Policy or discourse analysis/content analysis: Students should choose a topic of interest where they can critically examine relevant texts. If the topic is a specific focus of policy strategies, then the study should include analysis of policy documents. Other texts that can be a focus of discourse analysis can include media sources such as visual imagery and newspaper commentary. A number of public health issues have been the focus of discourse analysis, such as ‘food scares’, the spread of infectious diseases such as HIV, and students could consult published studies of this type for ideas. Students would also need to consult specific texts on discourse analysis for this approach.

A critical policy review (public health/primary care) utilising a suitable approach such as Framework Analysis. This qualitative research tool is used extensively in applied policy research. The process of framework analysis has five main stages:

- Familiarization

- Identification of a thematic framework

- Indexing

- Charting

- Mapping and interpretation

Qualitative research grant proposal

Students can also use qualitative methods as the focus for a research grant proposal, and simply follow the guidance specific to that approach described earlier in this handbook.

Bibliography

Clarke JN, Everest MM (2006). Cancer in the mass print media: Fear, uncertainty and the medical model. Soc. Sci. Med. 62 (10): 2591-2600.

Collins PA, Abelson J, Pyman H, Lavis JN (2006). Are we expecting too much from print media? An analysis of newspaper coverage of the 2002 Canadian healthcare reform debate. Soc.Sci.Med. 63 (1): 89-102.

Davin S (2003) Healthy viewing: the reception of medical narratives. Soc. Health & Illness. 25 (6): 662679.

Pilgrim D, Rogers AE (2005) Psychiatrists as social engineers: A study of an anti-stigma campaign. Soc. Sci. Med. 61 (12): 2546–2556.

Appendix VIII – Word Count and Late Penalties

Word count penalties for the dissertation will be applied as described in the Programme Handbook (MPH or MRes).

Word Count Inclusions

In accordance with accepted academic practice, when submitting any written assignment for summative assessment, the notion of a word count includes the following without exception:

- All titles or headings that form part of the actual text. This does not include the cover page or reference list (i.e. for a dissertation, the word count would start AFTER the Abstract).

- All words that form the actual essay (excluding the abstract and appendices)

- All words forming the titles for figures, tables and boxes, are included but this does not include boxes or tables or figures themselves

- All in-text (that is bracketed) references

- All directly quoted material

Word Count Exclusions

The following are excluded from the word count:-

- Title page

- Contents

- List of tables and figures

- Acknowledgements

- Declaration

- Intellectual property statement

- Text within tables and figures

- Abstract

- Appendices

- Bibliography/reference list

Late penalties for the dissertation will be applied as described in the Programme Handbook (MPH or MRes).

Appendix IX – MPH/MRes Programme Community Space

The MPH/MRes Programme Community space is the central place to access all programme-related resources and information and to communicate with other students across the programme.

It contains several essential courses, including:

Online Induction

The online induction course contains everything you need to get started on the programme by providing an introduction to, and overview of, the essential university systems and services. You must complete this short course before starting your studies.

Within the Online Induction course, you have the option to complete a Learning Needs Assessment. This questionnaire is to help you identify your own learning needs and to help us support you in achieving your goals. For further information on the way that The University of Manchester handles your information, please consult our student privacy notice.

Study Skills

The Study Skills course introduces you to a range of skills and resources required for developing practical and effective strategies for successful learning online. It includes topics on information searching, referencing and academic writing and requires you to complete the academic malpractice driving test.

Dissertations and Critical Literature Review

This part of Blackboard contains a range of resources to support dissertation students and those taking the option of a Critical Literature Review. It includes the calendar of workshops for Masterclasses and Tutorials for students at this stage in their studies.

Health and Safety Presentation

The university’s duty of care covers all its students, staff and visitors, including distance learning students who come onto campus for residential courses, study days or assessments. Although you will not spend much time on campus as a distance learner, there is some information you should know before you come. This short presentation tells you what to do in case of a fire or an accident while you are with us in Manchester. It should only take around 5 minutes to complete.

Both the academic malpractice driving test and health and safety presentation must be completed by 31st October 2021

Appendix X – Marking Framework for 2021/22

| Mark | Explanation | |

| 90-100% | Exceptional (allows award of distinction):

Exceptional work, nearly or wholly faultless for that expected at Master’s level. Perfect presentation. |

|

| 80-89% | Outstanding (allows award of distinction): Work of outstanding quality throughout. Excellent presentation. | |

| 70-79% | Excellent (allows award of distinction): Work of very high to excellent quality showing originality, high accuracy, thorough understanding, critical appraisal. Shows a wide and thorough understanding of the material studied and the relevant literature and the ability to apply the theory and methods learned to solve unfamiliar problems. Very good presentation. | |

| 60-69% | Good Pass (allows award of merit): Work of good to high quality showing evidence of understanding of the research topic, good accuracy, good structure and relevant conclusions. Shows a good knowledge of the material studied and the relevant literature and some ability to tackle unfamiliar problems. Good presentation. | |

| 50-59% | Pass: Work shows a clear grasp of relevant facts and issues and reveals an attempt to create a coherent whole. It comprises reasonably clear and attainable objectives, adequate literature review and some originality. Presentation is acceptable, minor errors allowed. | |

| 40-49% | Referral: Work shows a satisfactory understanding of the research topic and basic knowledge of the

relevant literature but with little or no originality and limited accuracy. Shows clear but limited objectives, and does not always reach a conclusion. Presentation adequate but could be improved. |

|

| 30-39% | Referral: Work shows some understanding of the main elements of the research topic and some knowledge of the relevant literature. Shows a limited level of accuracy with little analysis of data or attempt to discuss its significance. Presentation poor. | |

| Students starting their programme: | ||

| From September 2012 | From September 2016 | |

| 20-29% | Referral: Limited relevant material presented. Little understanding of research topic. Unclear or unsubstantiated arguments with very poor accuracy and understanding. Presentation unacceptable. | Fail with no opportunity to resubmit: Limited relevant material presented. Little understanding of research topic. Unclear or unsubstantiated arguments with very poor accuracy and understanding. Presentation unacceptable. |

| 10-19% | Referral: Limited understanding of the research process. The topic is largely without evidence to support its exploration for research and the arguments are supported by poor sources of evidence. The dissertation is disjointed and does not demonstrate logical coherent thinking with unacceptable presentation. | Fail with no opportunity to resubmit: Limited understanding of the research process. The topic

is largely without evidence to support its exploration for research and the arguments are supported by poor sources of evidence. The dissertation is disjointed and does not demonstrate logical coherent thinking with unacceptable presentation. |

| 0-9% | Referral: The text demonstrates no

understanding of the research process. The topic is totally inappropriate and there is no evidence to support its exploration as an area of interest for research. Presentation is extremely poor and is not in an appropriate format for submission as a Master’s dissertation. The topic would need to be reconstructed and totally rewritten if it were to be presented for resubmission. |

Fail with no opportunity to resubmit: The text demonstrates no understanding of the research process. The topic is totally inappropriate and there is no evidence to support its exploration as an area of interest for research. Presentation is extremely poor and is not in an appropriate format for submission as a Master’s dissertation. The topic would need to be reconstructed and totally rewritten if it were to be presented for resubmission. |

Download the full Dissertation Examiner Report Form here.

Appendix XI – Core Contacts (including technical support)

| Programme Administration | E-mail: mph.admin@manchester.ac.uk |

| Programme Director | Prof. Arpana Verma

Email: mph.director@manchester.ac.uk |

|

Dissertation Unit Leads |

Dr. Roger Harrison

Tel: +44 (0)161 275 5530 Email: Roger.harrison@manchester.ac.uk |

| Dr. Andrew Jones

Tel. +44 (0)161 275 1662 Email: Andrew.Jones@manchester.ac.uk |

|

| Deputy Programme Directors | |

| Dr. Angela Spencer –

(Student Support) |

Dr. Anjana Sahu –

(Curriculum) |

| John Owen –

(Technology) |

Dr. Isla Gemmell –

(Internationalisation) |

| Greg Williams –

(Innovation) |

Email: mph.director@manchester.ac.uk |

Technical Support

If you are having problems accessing My Manchester, email, your course materials, or you would like to discuss computer-related issues, please click the following link for 24 hour services:

http://bmh–elearning.org/technical–support/

If you are having difficulty with the electronic resources, you should contact the library via My Manchester.

IT Services Support Centre online

Details can be found at: http://www.itservices.manchester.ac.uk/help/

Login to the Support Centre online to log a request, book an appointment for an IT visit, or search the Knowledge Base.

- Telephone: +44 (0)161 306 5544 (or extension 65544). Telephone support is available 24 hours a day, seven days a week.

- In person: Walk-up help and support is available at the Joule Library, Main Library or Alan Gilbert Learning Commons

Technical Help with Blackboard

If your Blackboard course unit is not behaving as you expect, you can contact:

- The Course Unit Leader by email to get help with content issues (missing notes, etc.)

- The eLearning team for technical bugs using the eLearning Enquiry button via the following link: